Improving Work Zone Safety: Why We Should Consider Water-Filled Longitudinal Channelizing Devices

This 2011 Paper submitted by OTW Founder and Water Barrier Manufacturers Association Manager, Marc Christensen, along with association member Sreekanth Akepati, delves into the differences between concrete barriers and longitudinal channelizing devices. The paper is an interesting look at the current state of traffic barricades and industry safety standards and what could be a more effective path forward.

A paper submitted for possible presentation at the 91st Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting and publication in the Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board.

Abstract

In the United States an average of approximately 1,100 people die and 40,000 people are injured annually as a result of motor vehicle crashes in work zones. For addressing the safety in the work zones, a clear understanding of work zone traffic control devices and the dangers they pose to the drivers, pedestrians and workers should be obtained. This would be valuable for highway agencies in setting up proper traffic management plans based on the prevailing conditions.

The purpose of this paper is to educate transportation departments, consulting engineers, and others on the safety benefits of Longitudinal Channelizing Devices as an alternative to drums and temporary concrete barrier for work zone traffic channelization. The results show that the acceleration of vehicles in case of water-filled longitudinal channelizing devices is much less than concrete barriers, hence, the former proves to be a much safer and more efficient tool for work zone areas.

Introduction

As most of the nation’s highway infrastructure is aging, the current highway works have shifted from the construction of new highways to the maintenance and rehabilitation of existing roadways which in turn creates work zone areas. Majority of this reconstruction work occurs simultaneously along moving traffic which is also accommodated on the roadway under repair. Approximately 20 percent of the National Highway System (NHS) is under construction during the peak construction season. More than 3000 work zones are expected to be present on the NHS during the peak season. Hence, in this period proper traffic control is critical for safety in work zones. However, traffic control devices themselves may pose a safety hazard when impacted by errant vehicles. In New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT), 496 work zone crashes took place from 1994 through 1996, out of which one-third of them involved collision with work zone traffic control devices and 37 percent of those involving serious injury (1).

Improvements in our highway infrastructure will benefit all road users by creating safer roadways, providing jobs, and alleviating congestion. Our nation needs to build better roads, bridges, and transit systems without sacrificing the safety of motorists, pedestrians, and workers.

Projects may require numerous traffic control devices and other safety features on or adjacent to travel lanes. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), approved by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) as the National Standard, contains the basic principles of design and use of all accepted traffic control devices for all streets and highways which are thought to provide a safe work zone environment for construction workers and motorists (2). In this aspect, Longitudinal Channelizing Devices (LCDs) were first introduced in the 2003 edition of MUTCD, at the time referred to as longitudinal Channelizing Barricades (LCBs). According to the current version of the MUTCD, LCDs are described as lightweight, deformable devices that can be connected together to delineate or channelize vehicles or pedestrians.

Presently, Temporary Concrete Barrier have been specified almost exclusively into most construction jobs over the last few years. The consequences of using concrete barriers with regard to the dangers it causes to the motoring public have not been completely analyzed. According to Roadside Design Guide (3), published by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), “…a barrier should be installed only if it is clear that the result of a vehicle striking the barrier will be less severe than the crash resulting from hitting the unshielded object itself.” In comparison, LCDs are much safer in use than temporary concrete barrier, which, when impacted by wayward motorists, create high gravitational (G) forces that can cause serious injury and death to the driver and occupants of the vehicle. Yet roadway engineers increasingly rely on dangerous and improper installations of concrete barrier simply to prevent pedestrians or traffic from entering a work zone or closing a road. An overwhelming number of temporary barrier installations have nothing to do with shielding an errant vehicle from a massive object. Whereas LCDs are designed to give way and allow the vehicle to pass through the device, in turn keeping the G Forces from impact low and tolerable to the human body.

Hence, this study was performed to evaluate and compare the safety and economic benefits of LCDs with respect to the concrete barriers. Through this analysis an elaborate understanding of water-filled LCDs was obtained and its safety levels were also studied.

Water-Filled Longitudinal Channelizing Devices

The FHWA has accepted the use of several LCDs on the NHS from various manufacturers. While all of the accepted LCDs are considered crashworthy, as with all accepted traffic control devices, the test level for which each device is accepted varies. A review of the FHWA acceptance letter for the LCD being considered would let an engineer know what speed level the particular LCD has been tested to and the conditions under which the LCDs were tested (i.e., crash test level, evaluation criteria, with or without ballast, etc.) prior to adopting it for use in a particular situation.

“Although continuous line applications of LCDs may appear to form a solid wall, they do not meet the vehicle redirection requirements for temporary traffic barriers. Thus, while LCDs must be crashworthy, they do not provide positive protection for obstacles, pedestrians or workers. Since LCDs look very similar to water-filled barriers, the two devices are often confused with each other. To help reduce this confusion, Task Force 13, which serves the American Association of State Highway & Transportation Officials (AASHTO), Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) and the American Road & Transportation Builders Association (ARTBA) Joint Subcommittee on New Highway Materials and Technologies, has addressed this matter through the development of warning label guidelines that will provide users with sufficient information to discern between LCDs and barriers. It is anticipated that these guidelines will educate users about the performance of the different devices in order to avoid the unintentional use of LCDs at sites where actual barriers are intended. Task Force 13 and the American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) have approved the guidelines, and the FHWA has endorsed them. Task Force 13 is currently developing a website to disseminate the guidelines. The FHWA plans to include a link to the guidelines on its Crashworthy Work Zone Traffic Control Devices website (4).”

Unfortunately, LCDs have only been used to delineate pedestrian travel paths in work zones. As such, LCDs have ensured that the temporary pedestrian travel path meets the MUTCD accessibility requirements for persons with disabilities. Although LCDs are exceptional at meeting this requirement, there are other uses where LCDs are accepted by the FHWA, but are rarely considered. For instance, LCDs can be used in place of concrete barriers to close roadways to vehicular traffic. Closing roads using concrete barrier exposes motorists to extremely hazardous high angle impacts. Using LCDs to close roadways instead of concrete barrier mitigates this hazard. LCDs can be used to denote the edge of the pavement or separate the active travel lanes from the work area, where positive protection is not required. Again, using LCDs in this manner greatly reduces the risk to motorists and their passengers of an impact with concrete barrier.

In contrast to traditional channelizing devices (e.g., cones, drums, etc.) that have some open space between devices, LCDs can be connected together to form a solid line. Thus LCDs can prevent drivers and pedestrians from going between devices and entering the work area (whether inadvertent or deliberate). A solid line of LCDs also provides continuous delineation of the travel path, which may be beneficial at major decision points in work zones, such as lane closures, exit ramps, business access points (i.e., driveways) and temporary diversions (i.e., crossovers).

Of course, LCDs also could be used in a more traditional fashion. For example, in lane closures, single LCDs acting as Type 2 barricades (i.e., oriented 90° toward oncoming traffic) could be used in lieu of drums to form the merging taper. While the LCDs would not be used in a continuous line (i.e., there would be some open space between devices), due to their larger size the LCDs may still appear to form a solid wall to drivers approaching the lane closure in the closed lane. LCDs also are considered to be highly visible and have good target value, thus LCDs might increase the sight distance to the lane closure. In addition, the larger size of the LCDs may allow for increased spacing of the devices (i.e., more than one times the speed limit in mph); thus fewer devices would be needed (4).”

The current mind set of the safety community is geared toward using “positive protection” to protect maintenance workers in roadway work zones. As a result, concrete barrier has become the temporary traffic control device most commonly used in highway work zones. In fact, a recent survey of practices confirmed that temporary concrete barrier is the option most frequently used by state transportation agencies (5). When deciding on the correct and safe choice for temporary traffic control in a work zone, an evaluation of devices should place a particular emphasis on balancing the protection of construction and maintenance workers with the safety of road users traveling through work zones. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 101 fatal occupational injuries at road construction sites in 2008 alone. In 2007, 831 workers and motorists were killed in highway work zones and more than 40,000 were injured. Eighty-five percent of those killed in work zones are drivers or their passengers (6). According to an exhaustive report on 2008 traffic fatalities released by the Illinois Department of Transportation (7), there were 31 fatal crashes in work zones in which 31 people were killed. Only two of the persons killed were road construction workers, more than 93% of fatal injuries were to drivers and their passengers. Four out of five of the people who die in work zone crashes are motorists, not highway workers according to the Virginia Department of Transportation (8).

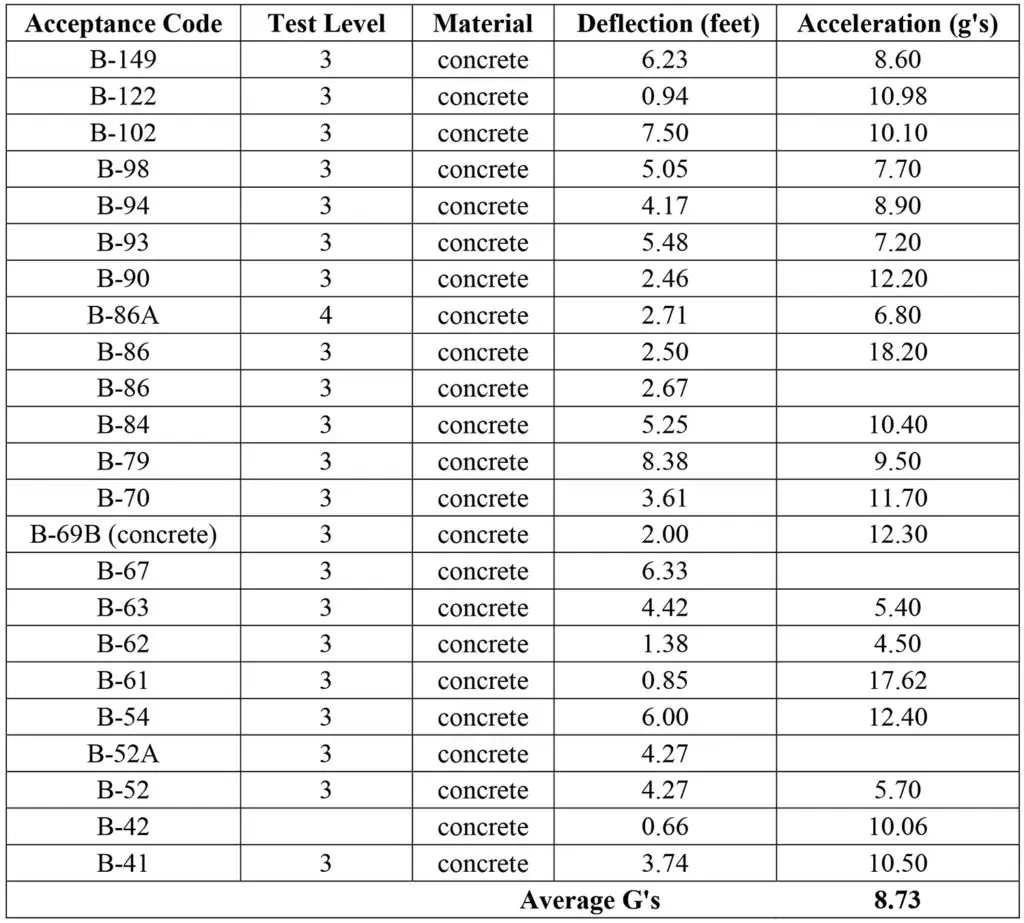

As stated in Part 6 of the MUTCD, “the primary function of temporary traffic control is to provide for the safe and efficient movement of vehicles, bicyclists, and pedestrians through or around temporary traffic control zones while reasonably protecting workers and equipment”. Traffic engineers expect these devices to improve safety for the motorists and reasonably protect workers when they are installed and maintained properly. However, the widespread use of concrete barriers, much of it for channelization and not positive protection, has been because the emphasis on safety has been on positive protection for workers, while 85% of fatalities are drivers and their passengers. These motorists and their passengers can be subject to average forces of 9.55 g’s and as high as 17.62 g’s shown in Table 1 (9) when impacting at 25 degree angles when traveling in standard size pickups.

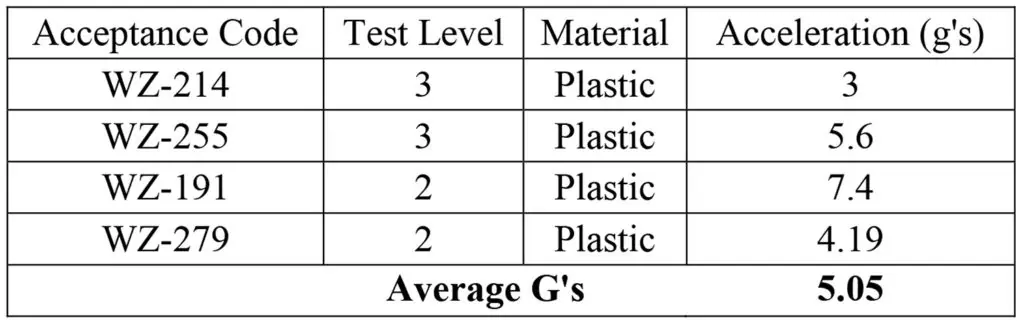

The same vehicle when impacting water-filled longitudinal channelizing devices at 25 degrees measured average ride-down accelerations of 5.05 g’s with the highest measurement at 7.4 g’s, shown in Table 2 (9). Keep in mind these angles are low and motorists can expect much higher forces when striking barriers that have been located perpendicular to traffic flow to close lanes. It is clear, when the crash test data is reviewed, that plastic water-filled LCDs create more positive outcomes in the event of an accident than the use of traditional concrete barrier due to the high G’s that motorists are subjected to when impacting concrete barrier.

The Roadside Design Guide urges temporary concrete barrier be placed only parallel to traffic (9). Most catastrophic crashes involving vehicles moving through the work zone and temporary concrete barrier occur when the barrier is struck at a high angle. Deploying temporary concrete barrier in work zones to close roads or to act as channelizing/delineating devices exposes vehicles and occupants to the possibility of engaging a massive object that can cause substantial injury and death. In this case, water-filled LCDs, which are designed to channel traffic without the risk associated with impacting a temporary concrete barrier, should be used.

TABLE 1 – NCHRP-350 Crash Tests Carried Out on Concrete Barriers

TABLE 2 – Crash Tests Carried Out on Water-Filled Longitudinal Channelizing Devices

If 85 percent of work zone crash fatalities are drivers and their passengers, and water-filled LCDs provide a higher degree of safety for the motorists passing through work zones, it would seem logical that water-filled devices would be the traffic control device of choice. Water-filled LCDs can be used even in cold weather conditions by mixing water with any of the sodium chlorides, calcium chloride, or more environmentally friendly additives like potassium acetate or BX36. But these devices are rarely, if ever used. In road construction work zones, resistance to change to use of water-filled LCDs (as with many devices new to the transportation infrastructure environment) slows industry-wide adoption of water ballast devices. There is an enduring familiarity with concrete and a tendency to rely on concrete barrier for every use, even when it is not the safest or most appropriate device for the job. Because there is no requirement or incentive for change, engineers simply continue to specify temporary concrete barrier for all traffic control jobs, in spite of the innovation of safer and more effective mechanisms. Findings show that deployment of new devices face roadblocks because (a) transportation projects are complex, multifaceted, and inter jurisdictional with many players having different interests; (b) multiple layers of decision making sometimes lack logic; (c) public-sector procurement is driven by competitive, multiple low-bid processes that often infringe on intellectual property rights; (d) public agencies resist change; and (e) risk-averse executives hesitate to implement new innovations (10). This research underlines the need for improved communication among researchers, developers, operators,and decision makers.

In addition to the institutional factors contributing to the lack of innovation listed above, there is no funding for innovative practices. If better safety costs more money, it must be funded. FHWA’s rule on Temporary Traffic Control (a.k.a. Subpart K) states:

“Payment for work zone traffic control features and operations shall not be incidental to the contract, or included in payment for other items of work not related to traffic control and safety; as a minimum, separate pay items shall be provided for major categories of traffic control devices, safety features, and work zone safety activities, including but not limited to positive protection devices, and uniformed law enforcement activities when funded through the project.”

To comply with this rule states create itemized lists of work zone devices. Unfortunately, innovative devices are rarely if ever listed. For example, the Longitudinal Channelizing Device, a traffic control device listed in the MUTCD for several years, is not listed in any of the itemized lists published by any State DOTs.

It is important to recognize that utilizing the full array of work zone traffic control devices available, and deploying suitable traffic control devices for each specific job, can prevent many accidental injuries and deaths in work zones. The continued reliance on temporary concrete barrier for every work zone application is extremely hazardous to the motoring public.

In addition, temporary concrete barriers also cause unnecessary work zone congestion 36 while they are unloaded and set into position by cranes requiring the closure of a traffic lane 37 for the installation. Manually unloading lightweight plastic LCDs, positioning them by hand, and adding a very small volume of ballast is much more affordable and does not require an additional lane for a flat bed and crane.

The four primary functions of barriers are to keep traffic from entering work areas, such as excavations or material storage sites; to provide rigid or positive separation for workers and pedestrians; to separate two-way traffic; and, to provide rigid or positive separation for construction such as false work for bridges and other exposed objects.

As noted earlier, temporary barriers are not traffic control devices in themselves; however, when placed in a position identical to a line of channelizing devices and marked and/or equipped with appropriate channelization features to provide guidance and warning both day and night, they serve as traffic control devices.

Longitudinal channelizes have been designed with several features that provide great advantages and benefits over contemporary traffic control devices. They fill the void in work zone traffic control devices that lies between concrete barrier, drums and barricades. The obvious advantages when compared to concrete are greater ease of handling, greater ease of installation, lower costs of installation, and fast setup time. At a minimum a four-person team must be utilized to run a crane, operate a tractor-trailer, and guide the heavy concrete barricade into place. When this cost is added to the purchase price of concrete barricade, tremendous savings are realized by utilizing lightweight plastic channelizing units. Not only is there price value, but also the lightweight plastic barrier will not damage expensive asphalt or concrete surfaces. In addition, the interconnecting plastic channelizing units do not require an expensive end treatment (a crash cushion that must be installed on the terminal end of a concrete barrier) as does concrete barrier.

Hence, temporary concrete barriers have many disadvantages, and alternative traffic control devices that do not pose a hazard to the motoring public and are more cost effective should be evaluated for best practice. Where guidance emphasis will suffice, a Longitudinal Channelizing Device is ideal. Longitudinal Channelizing Devices are lightweight, plastic, water-fill able devices that form bright, visually-compelling, continuous walls in the manner of concrete but without the lethal potential to impacting vehicles. The FHWA recognizes the need for LCDs and the MUTCD has been updated to reflect the useful and effective deployment of LCDS as an alternative traffic control device. See Section 6F.66 MUTCD.

Insubstantial traffic control devices such as folding Type I or Type II barricades, delineator posts, reflective panels and cones can be used in these applications as well, but are regularly ignored by aggressive drivers as the size of these devices is not formidable and the spacing between devices permits intrusion by vehicles. If drivers do not respect traffic devices, they may accidentally or even intentionally enter a work zone, causing injury to their passengers and/or workers. LCDs create a large and commanding traffic control device, compelling drivers to exercise more care in avoiding impact. Without this boundary, drivers may not realize until too late that insubstantial delineator posts were actually marking the edge of a very hazardous drop-off. The posts can also be confusing to drivers who often have difficulty determining their intended travel path through the widely spaced array of markers. This risk is increased when visibility is inhibited by weather conditions of heavy rain, fog, or other precipitation. Lastly, delineator posts, panels and other lightweight safety devices are often knocked over by passing vehicles, weather and the air backwash of heavy vehicles. An unbroken, interconnected array of LCDs provides a clear, unambiguous travel path, particularly where there may be directional path changes within a work-zone. In addition, LCDs connected together can also reduce the potential for missing devices as ballasted LCDs are more resistant to becoming misaligned by passing vehicles and weather.

Conclusion

For decades, road transportation departments, consulting engineers, and others who specify safety equipment in roadway construction projects have had few choices in traffic control devices. In order to reduce the number of work zone fatalities, these transportation professionals are urged to examine and consider new products offering vehicle occupants a safer environment. If 85 percent of work zone crash fatalities are drivers and their passengers, and water-filled longitudinal channelizing devices provide a higher degree of safety for the motorists passing through work zones, it would seem logical that water filled devices would be the traffic control device of choice. Preventing accidents and protecting workers, pedestrians, and motorists is a national concern. The way to ensure elimination of these tragedies is to encourage and require the use of the safest product for each specific job instead of relying on the most familiar traffic control devices or those devices already on hand for the project. Also, as the results show that the acceleration of vehicles in case of water-filled longitudinal channelizing devices is much lesser than concrete barriers the former proves to be a much safer and efficient tool.

Historically, engineers have specified temporary concrete barriers as a “one solution fits all” solution, and a culture has developed leaving temporary concrete barrier as the default option for channelizing delineation. Only when road transportation departments and practitioners begin to look beyond the familiar traffic control products will work zone safety be improved. The individuals most often overlooked when making traffic control decisions are the occupants of vehicles traveling through work zones. They are frequently exposed to the dangerous practice of utilizing temporary concrete barrier as a delineator or to close a road, elevating exposure to high angle impacts or required to drive through a confusing array of delineators, risking head-on collision. Those vehicle drivers and occupants could be your family or mine, so we must ask ourselves if we are really considering all of the available traffic control devices and how the proper deployment of these devices can create safe work zones, preventing injuries and perhaps saving lives. Surely, it is worth consideration.

The Authors

Sreekanth Reddy Akepati

Member

The Water Barrier Manufacturers Association

sreekanth.akepati@gmail.com

Marc Christensen

Manager

The Water Barrier Manufacturers Association

marc@otwsafety.com

References

- Bryden, J. E., L. B. Andrew, and J. S. Fortuniewicz. Work Zone Traffic Accidents Involving Traffic Control Devices, Safety Features, and Construction Operations. In Transportation Research Record: Journal of Transportation Research Board, No. 1650, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, D.C., 1998, pp. 71 – 81.

- Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. 2003 Edition, Federal Highway Administration, 2003.

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Roadside Design Guide. Third Edition, 2006, p.5-2.

- Finley, M. D. Roads & Bridges. Scranton Gillette Communications, February 2010, Vol. 98.

- American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA). Work Zone Positive Protection Tool Box. p.5.

- U.S. Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). FHWA-HRT-09-011, http://www.tfhrc.gov/focus/mar09/03.htm.

- Illinois Department of Transportation. 2008 Illinois Crash facts and Statistics. http://www.dot.il.gov/travelstats/2008cfweb.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2010.

- Virginia Department of transportation (VDOT). http://virginiadot.org/programs/WorkZoneSafetynewsroom.asp. Accessed on November 10, 2010.

- National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP). Recommended Procedures for the Safety Performance Evaluation of Highway Features. NCHRP3 350 Test 3-11.

- Orcutt, L. H., and M. Y. Alkadri. Overcoming Roadblocks to Innovation: Three Case Studies at the California Department of Transportation. In Transportation Research Record: Journal of Transportation Research Board, No. 2109, Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, D.C., 2009, pp. 65 – 73.